Contemporary architecture has increasingly been perceived as a process of continuous adaptation and permanent transformation. In this context, it has become common to describe it as “fluid”, shifting the idea of design from the realm of stability to one of decision-making. In architecture conceived in these terms, permanence becomes a choice rather than a given. This does not mean, however, that the fluidity of contemporary time allows for the emptying of cultural references that structure the urban experience; on the contrary, it requires greater critical and technical precision without losing its historical continuity. Sometimes, choices that confuse transformation with replacement materialise in the concrete loss of a work of cultural value, as has been the case in Florianopolis in recent years.

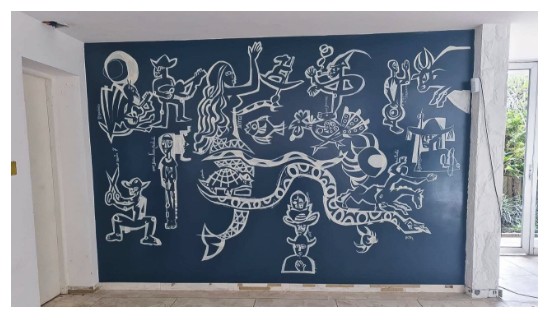

It is in this context that the recent demolition of a mural by Hassis, an artist from Santa Catarina, has reopened a debate that goes beyond the loss of a specific piece of art and exposes recurring weaknesses in the relationship between architecture, public art and urban regeneration processes. Born in Florianópolis in 1937 and passed away in 2001, Hiedy de Assis Corrêa, known as Hassis, was one of Santa Catarina’s leading visual artists, with national recognition and a career directly linked to the city. One of his mural panels, created in 1972, remained for almost fifty-five years on a building in the center of Florianopolis. Located on the wall of the former São Sebastião Eye Clinic on Armínio Tavares Street, the panel became part of the daily life of generations renovations, displacements and routines, but was demolished in early 2026 during a construction project. The destruction of the artwork highlights how contemporary processes of urban transformation still treat integrated art as a discardable element, rather than as a constituent part of the architectural project, public space, and collective memory (Figure 1).

Preserving Integrated Art: Technical Strategies and Precedents

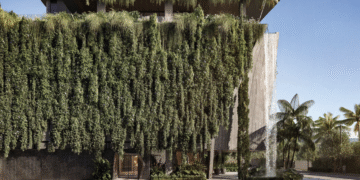

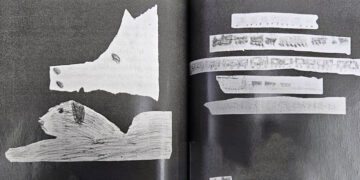

Contrary to what many recent interventions suggest, the preservation of murals, panels, and works of art integrated into architecture is not incompatible with retrofitting, technical modernization or change of use. Several buildings in Brazil and abroad demonstrate that the preservation of these pieces depends less on heroic decisions and more on conscious technical choices, incorporated into the project from the earliest stages. In Brazil, there are precedents of murals integrated into architecture that have gained technical and institutional attention for their preservation. In Curitiba and other cities in Paraná, works by artist Poty Lazzarotto remain preserved in public buildings and facilities, even after renovations and retrofits, demonstrating that the integration between art and architecture can be maintained even in the face of interventions and functional changes (Figure 2).

In contexts of total or partial demolition of existing buildings, the preservation of murals and panels integrated into architecture has been made possible through the adoption of independent support systems capable of isolation the artwork from the structural stresses of the original building. An emblematic example outside Brazil is the mural Tower (1987) by Keith Haring, in Paris, originally painted on an external staircase of the Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital. Even after the demolition of the wing that housed the work, the mural was restored and maintained as an autonomous element within the new hospital complex, now functioning as an urban landmark independent of the original building. A similar situation occurred in London, where a modernist mural by William Mitchell, created in 1958, was removed from a structure scheduled for demolition and relocated for relocation in a public space. The case, reported by the British press, demonstrates that the planned removal of the artwork, combined with technical support and conservation solutions, made it possible to preserve the panel even in the face of an irreversible process of urban transformation (Figure 3).

In addition to these examples, conservation studies conducted by institutions specializing in mural painting document recurring technical procedures for saving painted walls in risky situations, including controlled cutting of masonry, temporary structural reinforcement, and subsequent reinstallation of the art on new supports. These cases show that even when the original building cannot be preserved, the integrated work can remain as a material and cultural reference for the city, provided that it is incorporated into the technical reasoning of the intervention project.

If contemporary architecture deals with time as duration and not as absolute permanence, it must be recognised that fluidity does not equate to erasure. On the eve of Carnival celebrations, when Florianópolis reinvents itself through the intense use of public space, the demolition of a panel by Hassis shows how the uncritical celebration of urban fluidity can produce discontinuity, instability, and a loss of collective meaning.